MusiCirTechUs

Plenty of people who work in technology are musicians. Plenty of humans are musicians, and all of us are listening, even those who cannot hear. In my travels through datacenters and software, I have come across musicians like myself who have not only done double-duty with their computer science and creative lives but also relate and interweave them. If they’re like me, they cannot break them apart. There are hundreds, if not thousands, of us. We all have different stories, came into the worlds of music and of technology from different angles and different backgrounds.

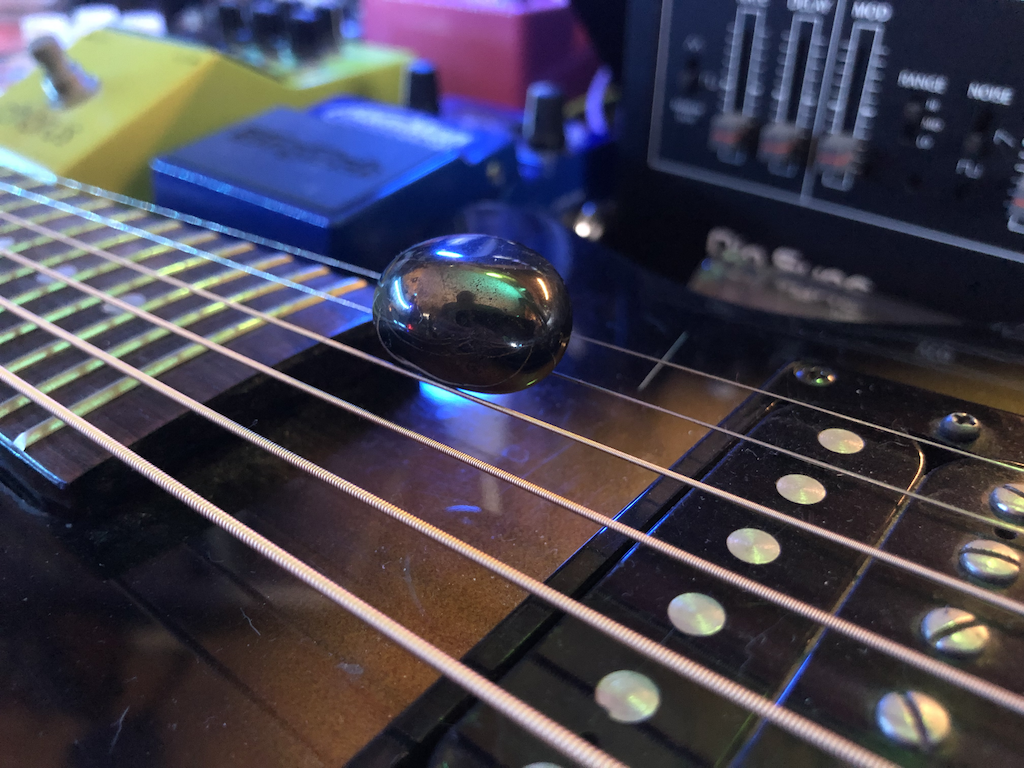

I’ll hazard a guess that when you think about the words music and technology together, it’s likely you’re thinking about music technology. This isn’t surprising, a great deal of music technology surrounds the production, performance, and recording of music. Musical Instrument Digital Interface (MIDI), studio recording, guitar pedals, analog control voltage synthesizers, DJ decks, Ableton Live, Max/MSP, Joe Armstrong running Erlang on Sonic Pi… the list goes on and gets fractally esoteric. All great examples of technology facilitating the art of music, but I’m interested in what’s happening the other way around.

The original impetus for this post was a comment someone made that raised an eyebrow… it made me briefly question the ideas I have about the field of resilience in distributed systems somehow relating to music. But humans share such an indisputably organic relationship with music and musical training that I knew I wasn’t just some crazy person, the connection was there and it was real. How else do I have the job I have now? This pushed me to want to find others that share my views on the close relationship music has with software and operational reliability.

Take Chloe Condon (Dev Advocate at Microsoft), a self-described recovering musical theatre actress. Now, my musical theatre training and tastes are

Recently chatting with her at SCaLE, Chloe clued me in about someone close to my wheelhouse: “Opera Singer turned Software Engineer” Catherine Meyers. Her Mozart could’ve been an Engineer talk correlates music theory and counterpoint to building software. She emphasizes the similarities of pattern recognition between the two disciplines, especially as it relates to learning. Preparing a new piece or constructing a score interpretation is 100% relatable to the software engineer learning a new language or building in a new framework. I especially love how she emphasizes the importance of having different types of minds together in one group, in other words, don’t be afraid to hire a music major.

These folks that are trained in synchronizing common ground through the experience of playing in musical ensembles carry a distinct advantage. Diversity and communication are the trademarks of both successful musical groups and software teams. Establishing common ground through shared learning is crucial to the modern team building and operating distributed software. It is obvious to me that ensemble music not only relates to complex systems but also to highly coordinated teamwork, to wit:

I’ve conducted marching bands, wind ensembles, and jazz bands.. . They are complex, highly interdependent systems.Tanner Lund (SRE at Azure)

This couldn’t be

In her blog post, The Origins of Opera and the Future of Programming, Jessica Kerr (Lead Engineer at Atomist) introduces the concept of symmathesy, a state of collaboration that is integrated with learning, all as part of the system (even the tools are team members). She does so by taking us back to the foundations of modern opera in Italy, adeptly adopting the term ‘

The CS / Math / Music crossover is clearly one I have encountered a lot, from early on. While I was studying voice and music technology in undergrad, I vividly remember walking with a good friend in downtown Blacksburg, and her saying to me “I could never major in music, there’s too much math.” I used to laugh at this because there’s really only as much math as that you wish to encounter. Want to dive into tempered tuning and Kepler’s mathematical ratios for perfect fifths? Go for it. But you know, these days I look at that statement through different lenses. Yes, there is just enough math! And if you study music, you may run the risk of studying computer sciences. * Please be aware that some practitioners of both have reported sudden bouts of inspiration and lightheadedness due to euphoric discoveries that cross disciplines.

On the subject of cross-discipline study…

I find a lot of what of I learned in music performance transfers directly to public speaking.

Amy Tobey (SRE at GitHub)

As a student of opera, I couldn’t agree more. Long ago I had a theatre teacher tell me “you will never be

When I gave my talk Measuring Distributed Databases Across the Globe at Southern California Linux Expo 13x (2015), a very enthusiastic artiste-cum-techie approached me afterward. They had decided to move into software engineering after art school and said my talk, which combines theories and ideas in music with those of observing and operating huge distributed databases, was inspiring. They had been trying to reconcile their internal ‘artistic identity and self’ with their passion for coding, and I had opened their eyes to a new way of considering it.

I will never forget this. It was exactly like having someone come up after one of my experimental music performances (which are also heavy with technology) being blown away and asking how things worked. Even if one mind out of a thousand is influenced by what I’m doing, whether it’s music or technology, I’m building the

Eureka! The audience contributes to symmathesy, too. There are tons of examples; the feedback of a crowd during a DJ set, participants of David Tudor’s Rainforest, someone opening a candy wrapper at the symphony. There’s no getting away from the audience, however small. John Cage preached throughout his career as an avant-garde composer: listeners are participants. Every performance is something new because there are different people in different places every single time. The title of this piece is a play on Cage’s Musicircus, an amalgamation of disciplines and performers occupying the same large space together with the audience.

So consider the sheer experience of music and how it feels oddly in-step with how we think about technology, and take it one step further. Many of us trained in the practice of music consider it so much a part of our bones that it seeps into our work, we don’t have a choice, the pattern recognition pathways seem to match up. They fit into our psyches in a comfortable way, share the same affinity for abstractions, incorporate complex and overlapping systems that stretch the human capacity for comprehension.

Do I have an aptitude for music because I’m successful in understanding the practical application of complex things? Or do I have an aptitude in technical operations because I have been trained in music and theatre arts? Doesn’t it make sense that the diversity of music is a human quality, not a disciplinary one? Why should our work as computer scientists, software engineers, database operators, and network gurus be any different?

Temple Grandin talks about the world needing all kinds of minds. In her view, different people fall amongst three “categories” of thought: Picture (common on the autistic spectrum), Pattern (code, math, music), and Verbal (writers). It resonates with me a great deal because I always feel like I’m thinking in ways others are not. More specifically, though, it underlines how different styles of thinking can bring entirely new perspectives on a particular question, and how crucial diversity is to human

This post started out as me being passionate about a subject and wanting to search for others who were. I had some bullet points of my own to insert, but as I searched and connected with others in the field, I learned new things and this blog transformed from a list of Twitter handles to real human relationships. I have grown to understand what Kerr means when she says that ideas are for sharing and collaboration, not hoarding and heroism. I for one am claiming my spot in the