To Build or To Buy, That is the Contradiction.

It’s dead simple. Focus on your team and product.

Yes! An easy tweetable answer! Except that it’s loaded with questions and assumptions. Instead, what I will talk about here are technology decisions. Those that really matter are about things that elevate your ability to build what you are building at the velocity you need.

In O

In my experience, it takes a minimum of six months for a team to work up a brand new (to them) technology or platform and have it be supportable in production. Even then, if the software team building it won’t be permanently oncall for it (which is something else I believe), they should at least be on the hook for a minimum of six months further as the kinks are worked out. This seems fairly straightforward for something like a development framework or a particular platform specific to operating the software system in question. For example, adopting Redis as a DBRE-supported platform in production. There are clear reasons why the software needs this kind of ultraspeedy k/v store, and building up widespread support in SRE for it means other software teams benefit. That is a highly opinionated decision and one that’s fairly easy to make especially because it’s free!

But is it? In contrast, what happens when you need to fulfill the needs of infrastructure? This is where Operations tires really hit the road. This doesn’t mean it’s a siloed decision, for example introspecting the system is as important to reliability engineering as it is to the folks developing the software. The Redis example above shows how technology decisions become a crucial part of the collaboration among everyone involved building your product, whether it be dev or sec or ops or everything in-between. However, it doesn’t quite reflect the reality of infrastructure requirements, particularly tooling that supports the needs of reliability. “We need monitoring and we need it yesterday!”

So, I posit: There is no “Build or Buy”. There is only Buy.

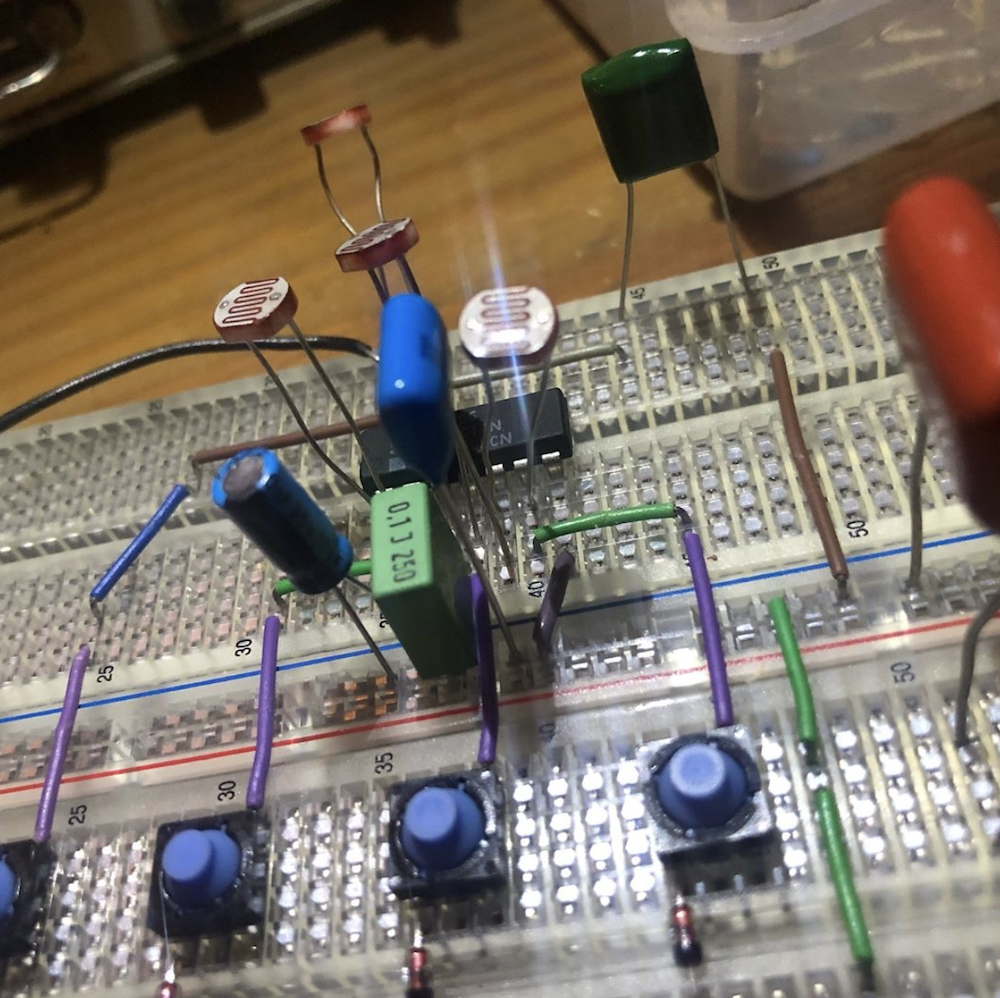

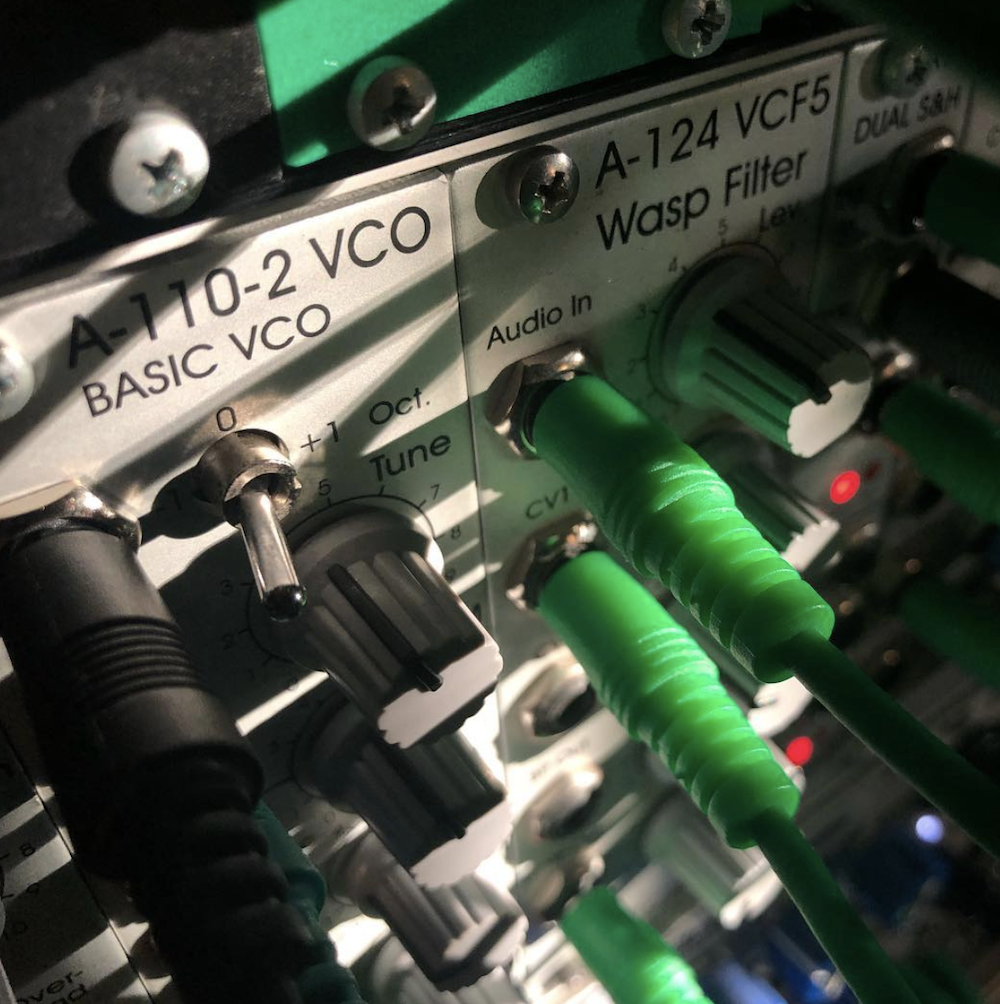

I build electronic instruments. My product is the music I make, and one the central philosophies in my approach to improvisation and performance is the concept of “original sound”. What music does a plucked cactus make when amplified, or how can a mercury tilt-switch and photoresistor create sound from electrons? The top picture here is of a breadboard, a prototype of a device that will eventually drive something called a “Voltage Controlled Oscillator”, or VCO. To the left is a photo of a professionally designed, tested, and built VCO. I have no need to design and build a VCO, even though fun, it is a distraction – both in time and money – from my main purpose: the creation of a new kind of analog synthesizer controller. I’d rather buy the VCO and the accompanying support of the experts who not only built it but are passionate about its success. Then I can focus resources on my creativity.

The technology decision to be made is heavily informed by what kinds of resources you want to spend on it. Building a platform in-house, using your own people, is sometimes only feasible with very large companies that have the ability to staff for this, and often have custom circumstances. It’s not hard to notice that a few very successful software platforms come out of organizations in this position. These teams also must deal with all the infrastructure costs, maintenance, reliability, and complex aggregations of data and transports. These problems have indeed been solved many times over by third party SaaS/PaaS/IaaS solutions, but sometimes the amount of customization required demands it. Or the development of these systems may be so clearly aligned with the company objectives that it is a non-question (e.g. Netflix pioneering Chaos Engineering or Google producing Borg/Kubernetes).

These days, such cases are the exceptions. Most of us are with companies where this luxury and concentration of engineering ability aren’t present. It may make a ton more sense to choose an expert in the field, whose company mission is specifically to provide this need. The argument that Ops Is A Cost Center is underlined

Either way, you’re building something. Recall the decision to choose Redis, and how long it took to enable that system in production. The same will apply to any in-house platform or tooling. Nevertheless, it’s a tradeoff. To buy resources for building in-house or

Like many in Ops, I once considered the “Elastic Search / Logstash / Kabana” (aka ELK) stack for datacenter log aggregation. All its various pieces are a fun complex thing to put together, and it’s an extremely useful resource for gathering and displaying events. All these pieces are freely available things, but our SRE teams were already pretty busy with the task of running our own product and other custom bits of infrastructure. It would take at least a single SRE’s full time and attention to keep the stack running across multiple server farms of 10,000+ nodes. Not to mention training and documentation for others. Maintained, tested, resilience-hardened, budgeted, the list goes on. I’m definitely going to be “buying” a lot here, and it’s a messy looking BOM. ELK’s competitors at the time ranged from fairly entry-level cloud-based SaaS to “Enterprise” packages, but one vendor, in particular, would be a great solution. Was there a cost and the administrative toil of negotiating a contract and keeping a vendor relationship going? Yep. It’s also a single invoice, takes much less time from the SRE team to manage, and is much simpler to integrate with the farm.

Would you rather focus on building the instrumentation into your software and have a team of external experts guide, consult, and ultimately provide the intelligence platform to which they have dedicated their careers? Or would you rather split focus and build your own customizations into the infrastructure? It’s not black and white, either. One method may outweigh the other depending on whether you’re bare-metal or in the cloud. There may be security reasons to do one over the other. As the software product matures, these needs may blur. What needs to be bought may be simple and small or complex and large, and grow in either direction.

So let’s be clear: a third party platform isn’t automatically “more expensive” than creating an equally performant service or fulfill a particular infrastructure reliability need in-house. Do the research and compare, make the investment that makes the most sense for your team.

Don’t be fooled, though. Either way, you’re buying it.