Am I developer?

Table of Contents

A decade or so ago, I am in a bar or something like it during some conference or another, and I hear someone say (verbatim, emphasis mine):

“Kubernetes is really going to help with the sysadmin problem, they just don’t understand development.”

I was one of those sysadmins. I did not understand development.

It’s my brain, I swear! Mine is wired for pictures and I have a strange dyslexia about words that has been there since childhood. I absorb words because of their look, feel, and sound. And that’s how my brain remembers them, but it also means that memory is extremely contextual. Holding abstractions about things I cannot represent in a picture in my head isn’t a thing I do well. I get so easily overwhelmed with “text” that all manner of it turns me away. Plus I’m just not good at math.

Unfortunately, all this helped put a big chip on my shoulder about me “not being a developer”.

Yep, DevOps#

You see, my tenure in tech has been tossed and troubled, and for a long time I felt victimized by the whole idea of “DevOps” infiltrating my carefully built catacomb of operations (it was only later that I realized I had been taught many of the best tenets of DevOps by being well-trained as a SysAdmin).

I made up my own assumptions and conclusions about it, how it did or did not fit my own worldview. It frightened me, actually. “DevOps” was making it difficult for me to find work. So when I was hired away from “system administrator” into a real “Site Reliability Engineering” role in 2013, I began my journey to Humble Engineer.

I took that quote about the sysadmin problem used it in a slide deck for a conference called RiCon about how scaling a system depends on more than just writing the code to do it. This was ten years ago, and I still misunderstood DevOps at the time, for the simple reason that it remained a demarcation in my mind. The walls of the silo were intact, just permeable. I gave my Five Principles of OpsDev, a tongue-in-cheek name I used to make the point that influence and cooperation flows in both directions:

- Don’t be the Angry Sysadmin, but question everything

- Reach back into dev, be present in their team, and educate

- Internalize rhythms of the data

- Provide the big picture, consider all angles

- Know the flavors of indeterminacy in the operation

Silo (not in the ground)#

In hindsight, my slip-up in that talk is that true collaboration is directionless. When teams say things like “they did this” or “the devs” or “that team wants” or “they won’t allow us”, they’re illuminating a silo wall (which, by the way, are not all visible, and they’re not all nice and round).

I can try to illustrate what’s on my mind by explaining the difference that I have seen in teams over my career. It is plain and obvious when teams are not hitting a good average for the “Three C’s” of Collaboration, Communication, and Coordination. Here are two amalgamated examples.

Design by Teams, Teams by Design#

Instead of waiting for the other side to make a move, we move like we understand that we’d move that way too. If we’re fostering a highly collaborative environment, we come to understand each other better, it feels less invasive for us to reach in and contribute. True reciprocal work is performed, empathy for coworkers across team boundaries is forged, insight is the fuel of innovation. We build relationships with and begin to tutor one another on our expertize. Knowledge is spread far and wide because the group takes every opportunity to learn from failure and retrospect success in shared spaces. Instead of one side or another, coordination becomes more cellular and operates conglomerations of diverse experts that have grown together to be an expert unit. This collective crosses corporate team structures all over the place because in building great interactions between ourselves, we build even better interactions in the technology WE build together.

Architecture with Parts that Don’t Match#

The flip side of this is a Functional or Information Silo. These are made by choice, to be managed in a hierarchical structure in order to control information. This disincentivizes workers to form cross-cleaving relationships because that would mean information is not flowing through official hierarchy, therefore not valid. Communication goes in and out the same way. Since workers have the experience that what they know about the rest of the org comes through this singular funnel, and what they do also must be communicated through that funnel, they tend to hinge their decisionmaking on ensuring the funnel is prepared for the communications that will have to be made. If that funnel is not available, decisions become waylaid. Workers who do not have all the information about what the other silos are doing tend to build their stuff in a vacuum to “best practices” because they have no other gauge, and members will complain about not being brought in on the design process early enough (they cannot, because of the silo). This leads to adopting “golden copy” practices without really considering whether they are actually needed by the architecture (about which they know only what the funnel has been able to tell them). They don’t know they can make decisions for themselves after being conditioned to check with the funnel on whether the decision can be made. There is camaraderie on the local siloed team, for sure. The effort to make meaningful connections with other humans in other silos is difficult because the opportunities are spread thin. In this mode, the “us and them” partition lives on, verbiage like “where do we draw the line” and “what THEY need” are used often.

There is no “They”, there is only “We”#

The social architecture of a siloed organization diminishes the ability of its workers to engage in connective labor. This not only contrasts the more flexible communal nature of the first example, it works against getting there.

You’re probably familiar with some of the outcomes of this. Instead of designing a product and integrating the best way for it to run, a solution is proffered and the design is relegated to infrastructure reasons that aren’t very clear, typically because they were decisions made in a silo. It is easy for that silo to point to “sources of authority” for why they are doing what they’re doing, but it isn’t so easy to point to the team that owns the interactions between the parts that are out-of-sync. This leads to endless problems about matching and coupling things, especially where the two silos meet in a moat of CI/CD, filled with alligators.

The lesson here is that Siloed Teams still work, they just take much longer to accomplish great things, because they are taking so long to do merely mediocre things. Meanwhile, more agile (yes I’m using that word) teams express more flexibility and balance between hunting down errors and formulating insight. The siloed teams miss out on insight when they can’t form relationships. Plenty of regular businesses still survive without insight. Innovative businesses do not.

So which are you? Ops or Dev?#

I used to quite emphatically proclaim that I AM NOT A DEV, but nowadays I’m better at writing apps in Golang than I am at putting together Terraform declarations.

I know and understand DevOps much deeper now, and when I look back at those Five Principles, they all still make sense to me. So there is something that I’ve always felt deep down about working in tech and building great things.

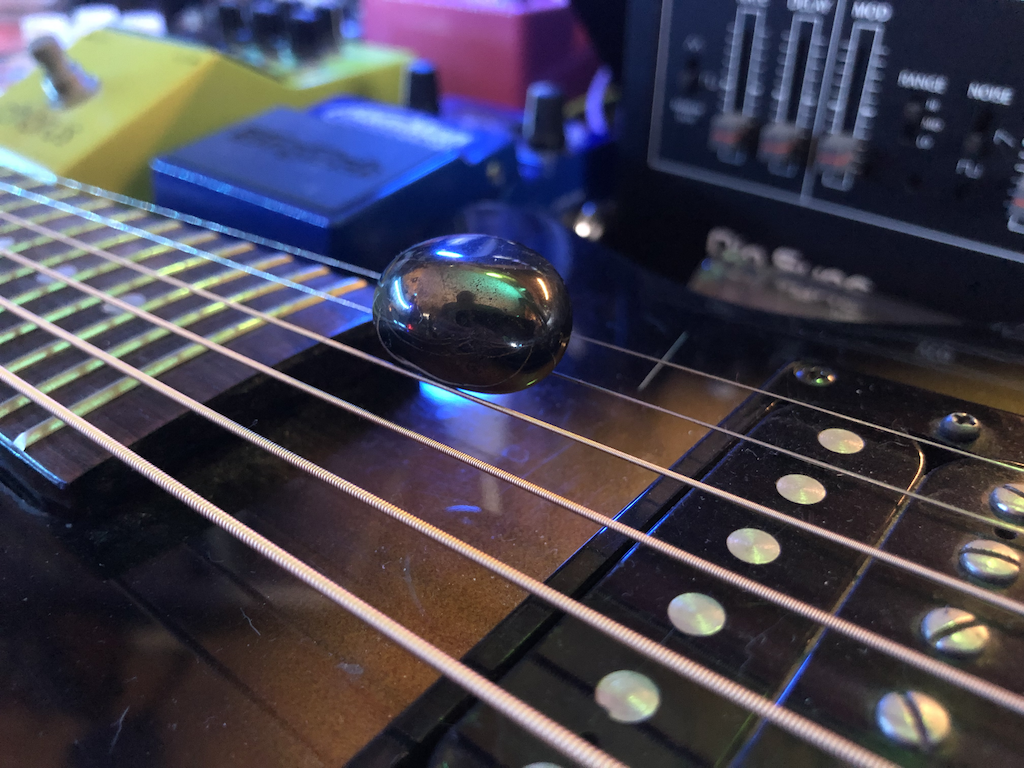

What I’ve learned is that the realization of what DevOps can be… well it is a journey. You cannot know it by reading a book. You cannot know it by working in just a few companies that “do DevOps”. It takes longer exposure. For me, it is accomplished through an ongoing study of Resilience Engineering, a discipline that tunes into my musicianship to give me lessons in complexity.

This path has led me to being embedded in DevEx teams and enabling my inner-coder with Test-Driven-Development. Someone asked me recently if I still wanted to be an “SRE”, and my answer was not immediate nor overwhelmingly positive. I like to build things, and I love tearing them apart to learn how they work. I do not like getting migraines over helm charts.

Whether I am an SRE or a Developer or a Software Engineer, maybe only time will tell. All of them make good music.